Back to News

Cool Jobs

Back to News

Cool Jobs

How a physical therapist ended up teaching physical education in Myanmar

Sometimes, after the sun sets, Aaron Saari (MVS ‘97) hears fighter jets flying over the Myanmar high school where he works.

Since the start of the school year, 200 of the 1,200 students have left, their families deciding to move out of a country decimated by civil war amid the reign of a military dictator.

Access to the truth is limited, heavily controlled by the government. Saari’s phone was stolen the other day, so it’s been even more difficult to stay on top of the news.

But Saari has always been up for an adventure. After all, he moved to Oregon from Michigan to learn to climb mountains. He traveled around the world as a physical therapist with the U.S. Nordic Combined Ski Team. He started a mobile physical therapy business that traveled to patients’ homes. And he earned a certificate in physical education so he could teach PE to children at international schools, including in Myanmar, where he and his wife have been living for the past three years.

“I'm beginning to understand that you can always reinvent yourself,” Saari says. “You just try a lot of stuff in life, and you never know when it’s going to suit you and help you out. It’s really about being present in the journey and the moment.”

Loving the content

Ever since Saari started playing hockey at 5 years old, he’s been interested in pushing his body to the limit.

He didn’t channel that love of physical exertion into a career at first. The University of Michigan was always his school of choice; he rooted for U-M sports teams growing up, and his older brother and sister had gone there. Their stories alone were enough for him to put all his “eggs in that basket.”

But Saari had no idea what he wanted to do for work, and he spent his first two years at U-M searching academically. The turning point was when he became a manager for the men’s basketball team, which boasted four of the five players who would become infamous as the Fab 5.

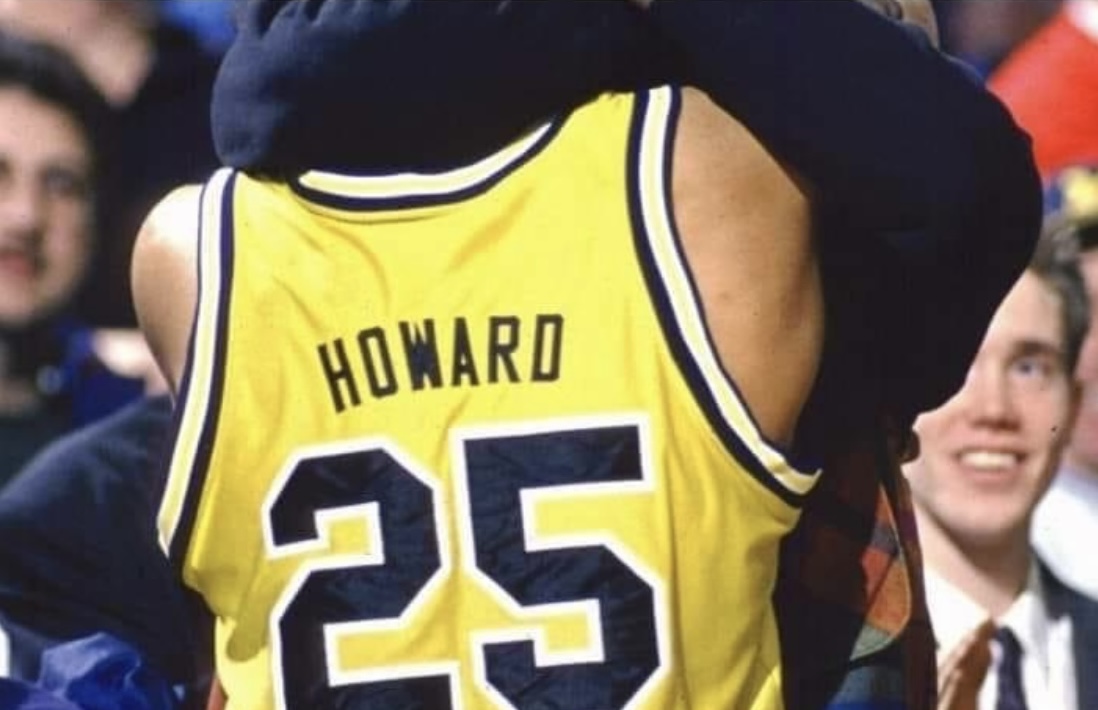

Saari as the basketball team's student manager is visible in the background as Juwan Howard, star U-M basketball player who'd go on to serve as the team's head coach, takes off a sweatshirt.

The students who worked as athletic trainers with the team told Saari about Michigan’s kinesiology offerings, and he was interested enough to transfer from the School of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) into movement science.

It was tough for Saari to balance his schedule as basketball manager with his challenging Kines courses, especially since he’d grown up attending a small school in the Upper Peninsula and says he didn’t have as much academic preparation as many of his peers. But he managed to study — in hotel rooms, on planes, from locker rooms.

“It taught me how to work really hard,” Saari says, “and I realized I could do well.”

Saari was fascinated by what he learned at Kines: exercise physiology with professor Jeff Horowitz, biomechanics with associate professor Melissa Gross, physical education with clinical assistant professor Kerry Winkelseth. He partially credits associate professor Susan Brown’s motor control classes for his decision to go into physical therapy.

“She and other professors would talk about physical therapists and what they do as a profession,” Saari says. “At the time, PT was a really hot career; people were hiring. I loved the content, but it was also a practical decision.”

And the travel bug had bitten Saari, thanks to the trips he’d taken with the basketball team not only to Big 10 schools but also to Hawaii and Madison Square Garden in New York City.

“That’s when I started to think, ‘There’s a whole lot more out there,’” Saari says.

The discomfort and the views

After graduating from U-M, Saari went to physical therapy school at Central Michigan University, worked as a PT in the state of Michigan for a few years, and then, as he says: “I wanted to learn to climb mountains.”

As a child, Saari had spent hours and hours outdoors in the forests of northern Michigan, which he and his siblings explored when their mother sent them out of the house to entertain themselves. When he read an Outside magazine story about mountaineering on Oregon’s Mt. Hood as an adult, he felt a visceral pull. Once he’d served out his final two weeks at his job, he packed up his car and started driving.

Eventually, Saari came to a crossroads, both literally and figuratively. Seattle or Portland? he pondered. He flipped a coin. Portland won.

After sleeping in his car and crashing on the couch of friends of friends for a while, Saari got a job at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). He moved to Hood River, Ore., and began climbing in the Cascade Mountains, content with the work-life balance he’d found.

“With mountaineering, there’s a challenge of exerting yourself and going through a lot of discomfort for a great goal, but there’s also the views,” Saari says. “When you’re standing on top of a big mountain, it feels like life’s really simple. It gets you right into the present. That moment is all that matters, and that feels very satisfying.”

Saari mountaineering on one of his favorite peaks in the Pacific Northwest, Mt. Shuksan.

Peaking at the right time

One day, a coworker at the orthopedic physical therapy clinic where Saari worked struck up a conversation. She worked part-time with the U.S. Snowboarding Team and had heard that the U.S. Cross Country Ski Team was looking for a physical therapist who could also cross country ski.

Saari had picked up the sport in physical therapy school because his then girlfriend’s family had been involved in cross country ski races. It reminded him of skating when he was a kid but with more endurance involved, a blood-pumping yet graceful motion that was endlessly enjoyable.

He wasn’t sure if he was adept enough to work with Olympians, but his coworker urged him to interview.

He was hired in 2006 and tasked with treating the nordic combined athletes.

“They do the ski flying,” Saari says. “And then after that, they’re placed in a cross country ski race based on how far they went and then they race to the finish. So if you jumped the furthest, you would start the race first.”

His job was to keep the skiers free from injury through standard techniques like massage, stretching, and manual therapy. But the coaches also wanted Saari’s opinion on the athletes’ biomechanics — were there any weaknesses or tightness that could be fixed or improved?

“That’s where some of the U-M training combined with the physical therapy really started to help out,” Saari says.

The nordic combined competitions lasted from November to April and took place mostly in Europe. Saari would travel with the skiers in vans from hotel to hotel, driving from Austria to Italy, up to Finland and back down to Germany and Czechoslovakia.

Every day, he trained with the athletes and then transformed his hotel room of the moment into a PT clinic to treat their aching bodies. He was even in charge of administering medications; if an athlete was sick, he’d call the ski team’s physicians back in the United States, describe their symptoms, and then give the athlete whatever medication the doctors prescribed out of his large, Mary Poppins-like bag. (“I don’t know if you could do that nowadays,” he quips.)

“It was very serious but really fun,” he says. “I wish that I could have sustained that kind of 24-7 pace for more than four years.”

At that four-year mark, it was time for the 2010 Winter Olympics. The U.S. nordic combined athletes took home four medals, including gold and silver in the individual large hill event and silver in all remaining events. The Americans had never previously medaled in the sport.

The U.S. Nordic Combined Ski Team celebrates their medals. Saari is pictured in the top left corner.

“To see them put in all that work and to peak perfectly at the right time,” Saari says, “it was a tearjerker moment.”

The tears flowed not only because of the skiers’ success but also because Saari was ready to move on. New athletes were joining the team and coaching changes were being made. Saari had been in a relationship with an American for a year, and the distance was wearing on him.

“It was a good time for someone else to jump on the train,” he says.

Beyond the clinic

Working with the nordic combined team had sparked an idea, though. Saari had realized he could offer quality physical therapy sessions using minimal equipment that he carried with him from place to place. Why not apply that concept to the general public?

“People are busy,” Saari says. “What if we just traveled to their office or their home or wherever they needed us to go and did our sessions there?”

And so, Beyond the Clinic was born. Saari opened the outpatient physical therapy practice in Portland with two friends and physical therapists he’d met at OHSU. They all had connections with physicians in the area, relationships that provided a small but steady source of patients. People liked Beyond the Clinic’s services, and Saari and co. were able to build the practice to 15 employees.

Even with success in their niche, though, profits were hard to come by.

“Because you had to drive to somebody and then see them and drive to somebody else and see them, you could only see so many people in a day,” Saari says. “We loved what we were doing, but numbers wise, it was tricky to make it work.”

Still, almost a decade passed. Then, in 2019, Saari’s mother and mother-in-law died of cancer. The losses prompted Saari and his now wife to consider how they wanted to spend the rest of their lives.

Saari's mother, who died in 2019 of cancer and served as his motivation to live life to the fullest.

They both loved to travel and were eager to do so again. Within a few months, they became certified to teach English as a foreign language, found jobs in Tongyeong, South Korea, and rented out their home in Portland. They thought they’d try the lifestyle for a year and see if they liked it.

Fairly quickly, Saari figured out that teaching English wasn’t for him. He enjoyed being around the students and even teaching in general, but the subject didn’t excite him.

Instead, he found a certification program to teach physical education, and he and his wife began interviewing for jobs at international schools, where the curriculum was in English.

Over and over, they heard the same thing: The interviewers loved the Saaris’ story but didn’t feel comfortable hiring them when they’d had so little experience teaching. Myanmar schools, though, were having trouble recruiting teachers given the tumultuous environment in the country. The Saaris were willing to take the risk.

Sharing what you learned along the way

The pair has loved Myanmar. Saari says the Burmese “people are wonderful, the food is great, and what can be visited in the country is beautiful” — all Buddhist temples and statues amid mountainous and jungle terrain.

A Buddhist temple in Myanmar.

And physical education has been a much better fit for Saari. He looks at the discipline as a way to tie together everything he’s learned — exercise physiology at Kines, physical therapy in Oregon, training with the nordic combined team. He simply has to make all the concepts interesting and relatable to his students.

“The main point is to try to convince them that it’s worth it for them to exercise,” Saari says.

So far, Saari has introduced the Burmese high schoolers to rock climbing, running, yoga, and meditation. He started a mountain biking club. He’s talked about nutrition. When he jammed his hand playing basketball and broke his pinky, he taught the teenagers about fractures — how to identify them on X-rays and how to correctly splint them.

Saari mountain biking in Myanmar.

He jokes that their biggest takeaway was that they’d have an advantage in the upcoming student-teacher basketball game because Saari couldn’t play. But in reality, Saari says, the students have been very receptive to the lessons he’s taught them.

“It’s gratifying to share all the stuff I’ve learned along the way,” Saari says, “starting at U-M.”

Fresh new options

Saari and his wife plan to temporarily move back to the United States once this school year is over (unless the fighting gets closer to their city, which will force them to leave earlier). They’ll likely stay in the Denver/Boulder area — the two met at a wedding there way back when — for a few months and then do a stint in Portland to see their friends and check on their house. Maybe they’ll stop by Michigan for a while.

Wherever they are, Saari hopes to pick up some travel physical therapy assignments while interviewing for a job at another international school. These types of teaching contracts usually last two to three years. So if all continues to go well, he and his wife will repeat this process, migrating between their teaching gigs in various countries and their home base in America for the next 10 or 15 years.

But maybe Saari won’t land another teaching contract. He has other ideas, namely selling medical or rehabilitation devices that are used in physical therapy settings. And if that path works out, he might try to shuttle the equipment to war-torn countries like Myanmar.

All of it sounds a bit like a movement-themed fairytale. But Saari, carefree and courageous as he comes off, says his life hasn’t felt that way.

“I felt the stress of making the right choices for most of my adult life,” he says. “And I’ve witnessed the high school students in Myanmar being extremely stressed about their college decisions, as if their entire life hangs in the balance of that one perfect choice. But in reality, every decision brings you down a different path with fresh new options that can be worth it.”

“The perfect decision and finally arriving at that perfect place is just a story in our heads.”